When the woven textures of Osaka cross the sea and unfurl the pleats of time within the exhibition hall in Zhujiajiao, Shanghai, Tsuyoshi MAEKAWA’s artistic journey becomes a channel linking the contemporary art scenes of East Asia. As a key second-generation figure of the Gutai movement, Maekawa has woven not only a narrative of innovation in abstract art through the warp and weft of burlap, but also a sustained inquiry into the evolving relationship between material and spirit in modern culture.

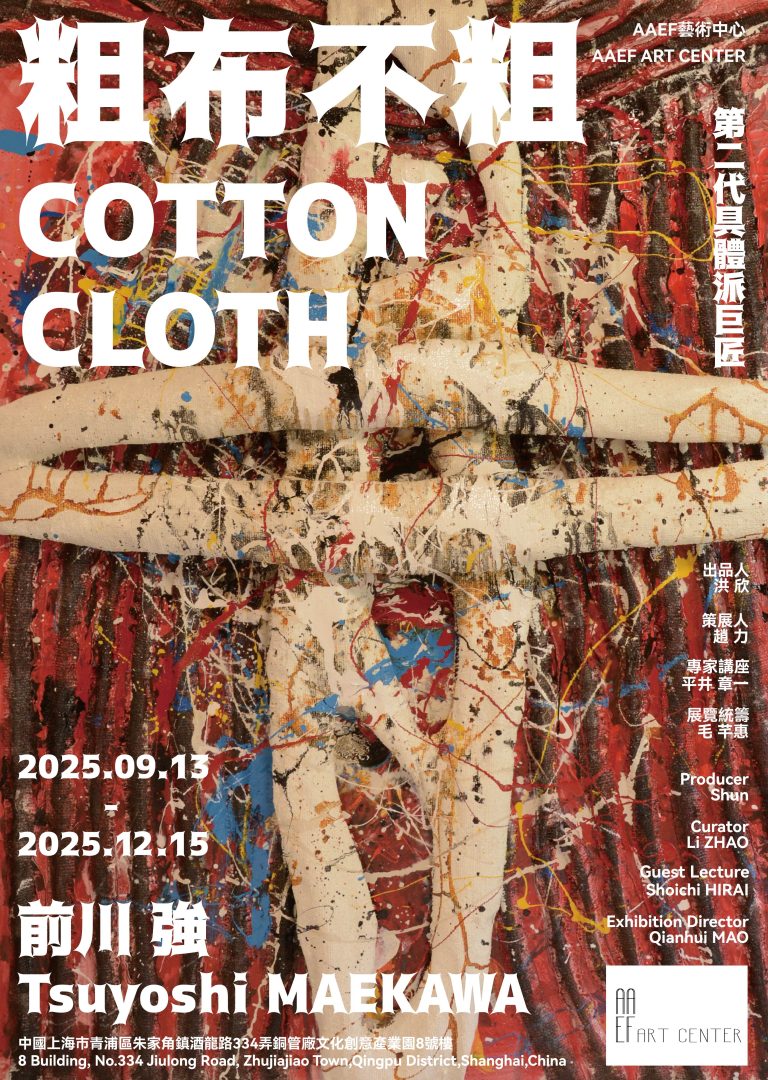

Born in Osaka in 1936, Maekawa’s artistic awakening resonated with Japan’s postwar artistic reemergence. When Gutai leader Jiro YOSHIHARA declared in the 1956 Gutai Art Manifesto “Gutai Art confronts the essence of matter,” “emphasizes the body and material,” and “advocating direct, concrete action,” the young Maekawa was already searching for breakthroughs in the coarse texture of burlap. By the late 1950s, he had abandoned the smooth foundations of traditional painting, fastening raw linen directly to the stretcher and letting splashes of paint and visible stitches turn the material itself into the protagonist of the work. This almost “sculptural painting” approach brought forth a spectacle in the art world—transforming cloth from a utilitarian object into a spiritual vessel, and making stitches an expressive force even more potent than brushstrokes.

From his Osaka studio to the exhibition halls of Tokyo, Maekawa’s trajectory has always been deeply bound to the practice of working through materials. In the 1960s, he glued spiraling woven forms into raised reliefs, their twisting lines evoking the mysterious markings of the Jomon-era pottery, yet reconstructed through the assembly techniques of the industrial age. In doing so, he injected the collective framework of Gutai with his own personal and sensorial reading of cultural history.

The dissolution of Gutai in the 1970s did not halt Maekawa’s progress. He turned instead to using a sewing machine to create embroidery-like compositions on soft cloth. The dense stitches became like markers of time, weaving microscopic universes across the surface. By then, Maekawa was no longer seeking the forceful collision of materials, but rather a gentler encounter with space through the shuttle of needle and thread.

In the 1990s, the introduction of acrylics added a new dimension to his practice. While maintaining the primal texture of burlap, he scattered bright blocks of color like light spots across the surface, striking a subtle balance between roughness and delicacy, weight and lightness. This evolution marked not only the maturity of his personal language, but also reflected the broader postwar Japanese journey—from reconstruction, to economic boom, to cultural introspection.

In fact, Maekawa’s art has never been detached from the soil of reality. In his burlap surfaces reside memories of an age of material scarcity, a commitment to the authenticity of materials in an age of mass consumption, and a meditation on the relationship between materiality and the bodily act of making. Now, as these works spanning more than half a century travel from Osaka to Shanghai, they offer more than just an occasion for cultural exchange. In Shanghai—a metropolis that has long witnessed collisions between Eastern and Western art—Maekawa’s work seems to find a certain resonance, seeking identity within the tensions between tradition and modernity, the local and the global.

Standing before the artworks, viewers gaze at burlap that has been pulled, stitched, and painted, experiencing the first-hand formal revolution of a Gutai artist, while also taking part in his ongoing inquiry into “What art can be”. Art can be the hum of a sewing machine, the breath of fabric, the dialogue between the automatism of gesture and the materiality of its support, or even the patina left by time on cloth.

In the current wave of digitalization, Maekawa’s work reminds us that the warmth of materials and the trace of the hand remain irreplaceable as spiritual mediators; that the humblest burlap can weave an aesthetic consensus that crosses borders. In the stitches from Osaka, in the gazes from Shanghai, we can ultimately read that the essence of art is to let the ordinary, tempered by time, become the eternal echo of an era.